by Mahsa Kalatehseifary

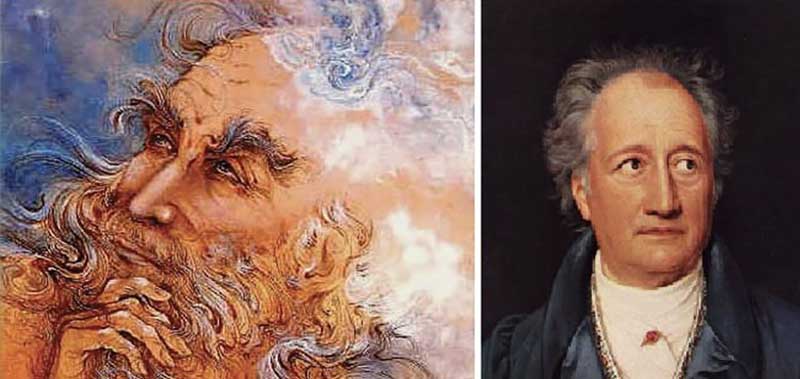

۳٫۱٫ An assessment of Hammer’s translation in light of Goethe’s poems

As mentioned in the previous chapter, Hafez’s poems revolve around three main thematic elements, which Goethe calls “elements of a real poem” in his poem “Elements” of the “Book of the Singer”. These are, in Goethe’s eyes “Love”, “Ruby of the Wine”, and “Poets’s hatred of hypocrisy”. Goethe went on to write that poems containing these elements would “refresh people and bestow everlasting contentment upon them”. Hammer too summarized these Hafezian elements in the foreword to his translation. His explanation there underlines Hafez’s hedonism and life-affirming attitude:

“He drinks light and wisdom from the eternal source of life, that is, from the source of eternal love…Often Hafez sounds somber as words of a Sufi, however he often mocks these teachings. He then dismisses the hypocrisy of Darvish alike, and praises places such as taverns. He does not see in parables of Eden and afterlife, images of the beauty of his beloved and happiness of life, so he calls onto taverns and barkeepers, and places teachings in the mouth of roses and nightingales.”

Taking Hafez’s bacchanalian approach toward figures of religious authority at face value, Hammer magnifies the Divan’s libertine aspect by devaluing other aspects of the poems, such as their mystical implications. Based on the dramatis personae of Hafez’s Divan, as presented in the first chapter, I have selected two complete poems and a number of single distiches containing Hafezian characters to demonstrate this point. Verses from Goethe’s West-östlicher Divan with similar contents are then examined in order to determine the extent to which Hafez’s message came through.

۳٫۱٫۱٫ The pivotal function of Hafez’s Rend

Rend, Hafez’s impersonator in the Divan, plays a pivotal role in the activity and development of other poetical creatures of his universe. The figure functions as an antithesis to hypocrites named throughout as Sufi, Darwisch or Zahed [zealot], whose approach Hafez considers to be ascetic. By acting as an advocate for love, wine and other elements forbidden by the ascetics, Hafez’s rend communicates the author’s strong opposition to them. Therefore, as Hafez’s spokesman, he condemns their strict dogmas and shows his own intense yearning for his Zoroastrian ancestors. He longs for them as his “spiritual role models”, whose “appreciation of reason, life and happiness rejects blind faith and [a] slavish approach towards any authority [that] make[s] … a world … tolerate deceit, violence and cruelty”. In the section “Persians”, Goethe recognizes Zoroastrianism as “noble, pure, nature religion” and elucidates the rituals and teachings of this Persian ancient creed, which he further examines from an historical perspective in the poem “Legacy of Old Persians” in the “Book of Persians”.

In ghazal eighty six of the group Ta, Hafez as writer-emancipator rejects the tenets of his clerical society. This ghazal is one of few that he versified on the occasion of the end of Ramadan, a time of celebration when taverns reopened and drinking wine was again allowed. Furthermore, it is one of very few ghazals in which the repetition of the word rend throughout the poem indicates the focal role of this figure for the overall message. Hammer’s translation of the poem has eight distichs. Here is the first: Fasting is over! Celebration is here! Hearts are flowing with joy,

Wine flows in barrels, its now time to demand. Hammer divides a distich into four hemistichs in his translation of the majority of ghazals. In this poem his translation succeeds in achieving the metrics of the original by rendering the distichs in two hemistichs. His attempt to maintain the fundamental metric rule of the ghazal, the rhyming pattern “-en” of the first hemistich fails in the original German translation, as it is not sustained throughout the poem. Semantically, the first hemistich of the translation transfers the meaning despite the fact that Hammer pluralizes “Fasten” in his German rendering. This can be considered as the result of Sudi’s interpretation of the distich, in which he uses “Ramadan days” instead of the original singular noun for “fasting”. ”. In the second hemistich, however, there are semantic deviations from the original which are not the result of Sudi’s commentary. The first clause of this hemistich in the original talks about the tavern, in which wine “flows”. The choice of the verb “to flow” works well in this clause, since it recalls the thematics of the last clause of the previous hemistich: in the reader’s eyes the “flowing” of wine in the tavern enlivens “flowing of happiness in hearts”. Hammer omits three literally-translated “and”s in the first hemistich and one in the second to avoid repetitive hiatuses.

To be continued…