Writer: Shardad Khabir

Once upon a time, in the streets of Tehran, the voice of the Left rang with the promise of justice. From labor struggles to anti-imperialist slogans, Iranian leftists in the early twentieth century saw themselves as heirs to ideals meant to build a society of equality and freedom. But today, that legacy has faded into a shadow of the past, tangled in theoretical and discursive crises.

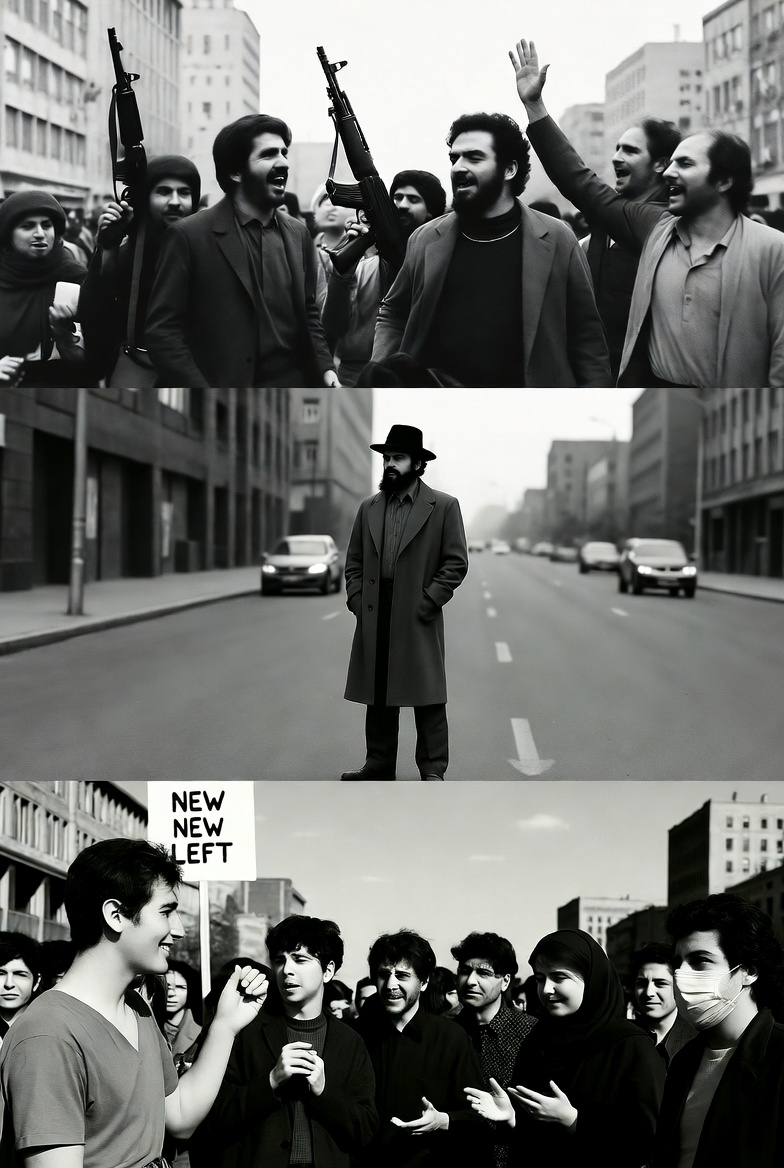

Traditional Iranian leftism, rooted in classical Marxism and revolutionary experiences of the twentieth century, emphasized public ownership, state centralism, and social revolution. Yet with the collapse of the Soviet Union and sweeping structural changes in the global economy, many of its core assumptions were called into question. Its focus on the working class seemed ineffective in a society whose economic structure had fundamentally shifted. Anti-imperialist rhetoric grew confused in the face of globalization’s complexities. And its inability to respond to gender, ethnic, environmental, and cultural demands pushed the traditional Left to the margins.

In the 1990s, a new Iranian Left emerged. Drawing on translations of the Frankfurt School, neo-Marxists, and Western cultural theorists, this movement sought to reconstruct leftist discourse. Economics was no longer the sole axis of analysis; identity, language, power, and culture took center stage. Yet this New Left faced serious criticism. Its discourse, rather than being rooted in Iranian experience, was largely imported and derivative. In confronting Iranian identity, it sometimes resorted to extreme labeling—accusing it of fascism or chauvinism. Internal contradictions and theoretical conflicts deprived the movement of cohesion and social impact.

Perhaps the most significant crisis facing today’s Iranian Left lies not in its external rivals, but within itself. Traditional and New Leftists lack a shared language and often stand in stark opposition. One clings to social revolution and class struggle; the other to linguistic critique and cultural theory. One draws from local experience; the other from translated Western frameworks. And in between, the Iranian public finds itself adrift between two disconnected discourses.

But this crisis is not unique to Iran. Across the globe, in the United States, the New Left has written a different story. Since the 1960s, through student movements, anti-war protests, and civil rights activism, the American New Left has taken shape. Unlike the traditional Left, which focused on class struggle and political economy, the New Left turned its attention to cultural, gender, racial, and identity issues. Initially distant from the Democratic Party—and at times viewing it as part of the “power structure”—many New Left activists gradually entered formal institutions, including the party itself.

Over the following decades, the New Left slowly embedded itself within the Democratic Party’s internal coalitions. First through academia and cultural institutions, then through policy platforms. Its focus on racial justice, LGBTQ+ rights, police reform, and structural inequality now defines key aspects of the party’s agenda. Figures like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Bernie Sanders, and Ilhan Omar represent this current from within.

Yet this influence has not come without cost. Moderate and conservative factions within the party have at times accused the New Left of extremism, impractical idealism, or alienating traditional voters. These tensions have surfaced in primaries, debates, and policy disputes. From a fringe movement, the New Left has become a cultural and intellectual force shaping the party’s future—though it still grapples with challenges like maintaining unity, engaging traditional constituencies, and confronting political polarization.

Polarization, however, is not merely a political challenge—it is a cultural crisis that has erupted into violence in America’s public sphere. In recent years, groups like Antifa, under the banner of “anti-fascism,” have become symbols of radical leftism. Lacking formal structure or hierarchy, Antifa rejects dialogue in favor of direct, often violent action against those it deems fascist or racist. Public figures such as Charlie Kirk, Jordan Peterson, and Ben Shapiro have faced threats, cancellations, and even physical attacks.

Charlie Kirk, a conservative activist, sought to create platforms for dialogue. But in a climate where conversation has been replaced by labeling and exclusion, his efforts were often met with hostility. His assassination, more than a personal tragedy, became a symbol of the collapse of discourse in a society once built on free speech. The New Left, despite its achievements in social justice, now faces serious challenges in preserving a shared language and civic engagement. Conservatives, meanwhile, feel threatened by identity-based narratives and seek to reclaim public space.

In the end, perhaps the most urgent question is this: Can our societies—whether in Tehran or Washington—return to dialogue? Or have violence, exclusion, and ideological branding permanently replaced understanding and coexistence? The answer will shape not only the fate of Left and Right, but the future of democracy and public culture itself.